27 November 2025

From Glasgow 1965 to Shanghai: a Champion reflects on his legacy at the WorldSkills Museum

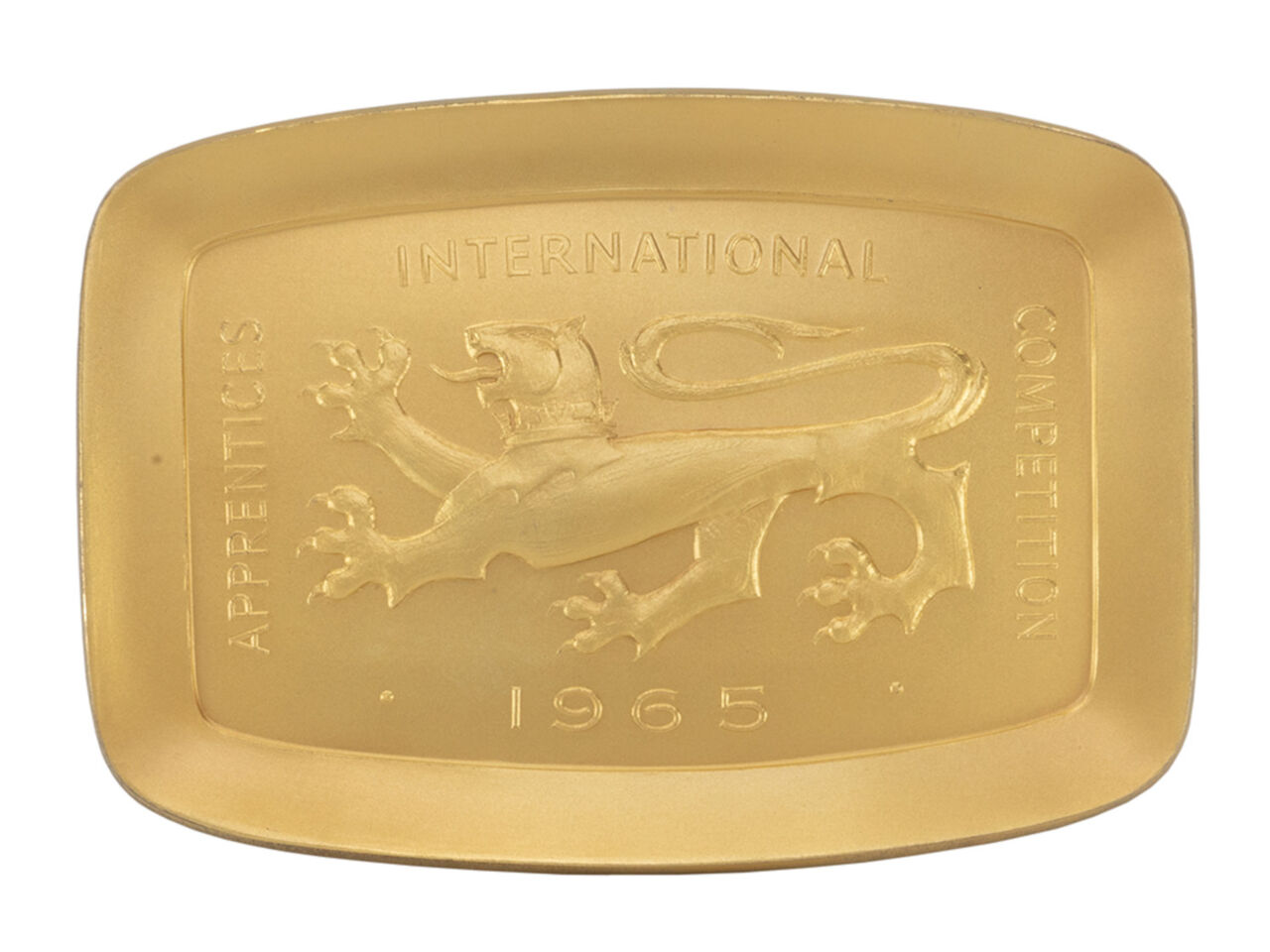

Sixty years on, WorldSkills Champion and Master Silversmith Peter Johns travelled to the WorldSkills Museum in Shanghai to see his gold medal, prompting memories and hopes for the future of skills.

Peter Johns, 81, won gold in Silversmithing at the 1965 International Apprentice Competition in Glasgow. Standing before his medal in the WorldSkills Museum marked a powerful moment of reflection for this former Competitor. He says, “That young boy from London would have never imagined this 60 years ago!”

He continues, “It is hard to believe that I am in China looking at something that I was involved in, in the UK, all those years ago. It makes me realize that I am part of something so much bigger than me – and something that is likely to be around for so much longer.”

Peter was one of many young people who helped shape what would become the WorldSkills movement. Now, his winning medal, a congratulatory letter from Prince Philip, his Competition coat badge, and an archival interview form part of a permanent display in the museum’s gallery dedicated to “Celebrating a Successful Global Movement”.

Seeing his items in the exhibition reminded Peter that he took away more than a gold medal from the Competition in 1965. He remembers, “Winning was not just about the joy. It was something that gave me confidence. I think that’s the main thing. You know you’ve been tested and you’ve come out okay.”

Peter’s trade, Silversmithing, is no longer an official WorldSkills skill competition but, much like the Jewellery skill competition now, it demanded meticulous craftsmanship. Machines were not permitted, so the skill required manual precision, patience, and problem-solving under pressure.

“I feel these are the qualities that lie at the heart of WorldSkills. The Competition asks young people to do exactly what the real world demands: face something unfamiliar, figure out how to tackle it, and then deliver it under pressure to a high standard. That’s the essence of working life. If I could, I’d put that message on a banner in the WorldSkills Museum,” he says.

Back in the 1960s, Peter was originally on a path to become a toolmaker. But an encounter with a silversmith through The Scout Association took him in a new direction. After attending The Central School for Arts and Crafts in London, he started an apprenticeship and has been an advocate for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) ever since.

He shares, “I have great belief in TVET. It teaches you more than just the technical knowledge you’re learning in that moment. It teaches you coordination between your brain and your hands. And then you can turn your hands and your brain to anything else, because you understand how things are put together.”

Throughout his career, Peter made every effort to pass on his knowledge by training the next generation. He worked in the industry for several years before moving into graduate training at Middlesex University in north London. He was pleased to see how the Art education system of training continued to evolve, with more freedom and opportunities for students to engage in hands-on work, producing many top designers and craftsmen for industry. He is still involved in training using Argentium, a new silver alloy which he invented in the 1990s. It is hailed as the most significant development in Sterling Silver for more than a hundred years and today is widely used to make silver jewellery.

Modest about his own achievements, Peter talks proudly of his students’ careers, saying, “Many of them have opened their own businesses and now sell their work online. One even went into film prop making and was very successful. Skills give people plenty of chances to make a living. Learning to do something useful with your hands leads to other skills and other crafts.”

Peter’s visit to Shanghai reconnected him with his WorldSkills legacy. It also connected him to the thousands of young learners who visit the WorldSkills Museum each month, and who will one day shape our world through their skills.

He admits that life for these young people is unrecognizable from the professional world he entered 60 years ago. Seeing them walk the halls of the WorldSkills Museum, he emphasizes how important it is to remain responsive to change. He reflects, “I hope I stay open-minded enough to adapt to these new technologies which happen to come into the world as I still explore it.”

In this 75th anniversary year, Peter feels incredibly proud that his medal is part of WorldSkills history and has a place in the WorldSkills Museum. But he knows that his experience is just one small part of the story, and that the strength of the WorldSkills movement lies in the next generation of talent.

“It really is not about the guy or girl who finishes up with the gold medal. It’s about all the thousands of people who aspire to that,” he says.

Visit the WorldSkills Museum website and explore the WorldSkills Archive.